Soap Wars – Surf, Nirma & Wheel

There was a time when fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) businesses ruled the marketing landscape and HLL (Unilever) was the unchallenged ruler. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, Nirma and Karsanbhai Patel showed up in the 1980s. When Nirma’s popularity began to rise, even Lever couldn’t stop it. Lever had never been so thoroughly undermined before.

Nirma cost one-third as much as Surf. Nirma was 7 rupees per kilogramme, whereas Surf was 21. Karsanbhai, critically, out marketed Surf by taking a page from the HLL marketing playbook. One of the most clever marketing efforts was Karsanbhai Patel’s bottom-of-pyramid strategy (much before CK Prahalad coined the phrase).

Nirma was more than simply a local favourite, but Levers’ executives didn’t see it that way at first. There was a group at Surf tasked with lowering pricing to compete with Nirma; they dubbed themselves C.R.I.S.P. -“Cost Reduction in Surf Prices.” And thus, the seeds of Operation S.T.l.N.G. were planted.

Strategy To Inhibit NIRMA’s Growth (S.T.I.N.G.)

The business expansion was not the issue; rather, it was survival. To someone unfamiliar with India’s detergent industry, it may seem like a bold claim. But in reality, it was an admission that the rules of the game had changed without their knowledge. Mass market detergents now accounted for 80% of volumes and 68% of value, up from 70% when Surf first entered the market.

Choosing the name “Wheel” itself was not a deliberate move; it was more of a result of necessity. International brand launches were not simple back then due to the strict laws that were in place. Years before in 1987, HLL had introduced a detergent bar named Wheel, but it had to be scrapped because of poor sales. However, due to legal constraints, they were limited to choosing a name from an existing pool and ultimately settled on Wheel.

HLL formed a team outside the firm to storm Nirma’s bastion and win the war. Given that Wheel was Hindustan Lever’s first low-price product, the business opted to implement a new kind of management. For example, wheel operations were run out of Chandigarh, while the rest of Hindustan Lever was based in Mumbai. They envisioned Wheel as a successful enterprise in its own right

Reaching Out To The Masses

The top brass back then realised the value of reaching out to the masses

The first major obstacle was developing a cheap product that met all of HLL’s quality requirements. HLL realised it was time to abandon the notion that multinational corporations (MNCs) would never offer low-priced goods. Low-end did not always mean low quality.

The customers said they could not afford Surf. Consumers wanted inexpensive cleaning products, and the challenge was to provide both a suitable product and the necessary supporting infrastructure to meet this need. Other factors, such as marketing, price, and distribution, played a crucial role when low-cost competitors were ruling the roost.

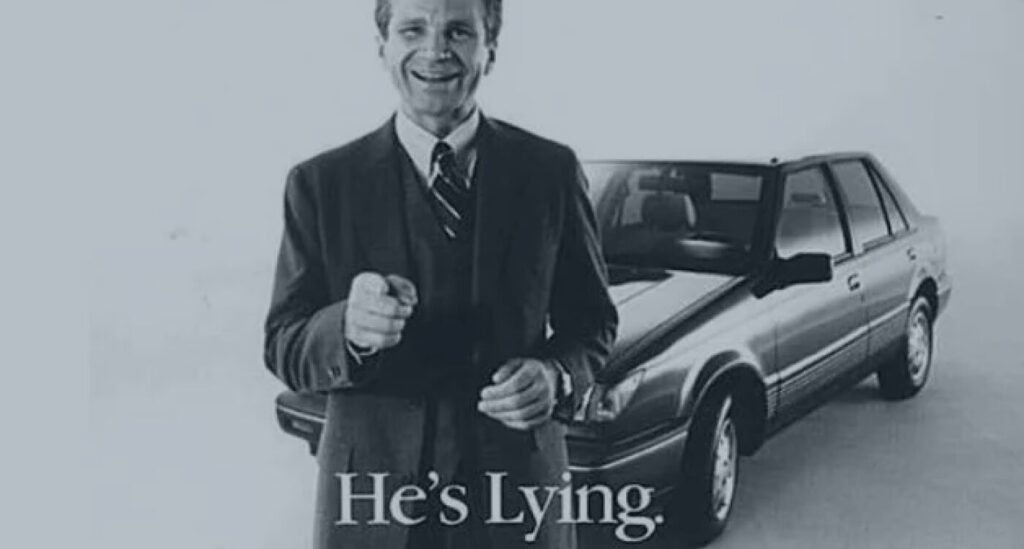

Advertising agency Lintas for Surf tried to compete with Nirma with the now-iconic tagline “Surf Ki khariddari mein hi samajhdari hai.” However, the advertiser and the agency agreed that such a position would be detrimental to Surf in the log run. To counter Nirma where it thrives in the market, a lighter brand was required. Surf’s value might drop if it’s used in that fight. Attempts to use Sunlight, which has little popularity outside of the east, to counter Nirma were likewise unsuccessful.

Levers also made several significant firsts in this area. Previously, in-house manufacturing had been the mainstay of the business, but this time around, the corporation relied heavily on outsourced production. Next, whereas HLL’s whole portfolio had fixed prices, Wheel went with variable rates. Prices might vary from state to state because of variables such as the level of competition and taxation in each jurisdiction.

The uneven nature of the competition was also helpful. Wheel’s success may be attributed to the company’s use of HUL’s formidable distribution network to reach customers anywhere in the nation, no matter how out of the way.

The second major difficulty was communication since back then, Lever’s ads for detergents invariably featured stereotypically white-sari-clad women. Nirma shook things up by having its youthful audience chant, dance, and jump to an upbeat tune.

It was agreed that Wheel’s marketing would be unconventional. Levers’ legendary Dekho Dekh Dekh jingle, with its riot of colours and crazy dancing, was created as a response to the Shiamak Davar dancers’ swinging to Washing Powder Nirma.

A fascinating consumer insight was identified by HLL, and a fantastic commercial was created by Lintas, allowing the brand to finally reach its stride. The realisation was that many people who used Nirma had painfully hot hands. Nirma’s high soda ash concentration made it harsh on the skin and nails. Even so, doing so was not a breeze. because people often believe that if a powder burns, it must wash nicely.

This epiphany resulted in the Maine maangi thi safaai, aur tu ne di haathon ki jalan commercial. And now it was rocketing toward Nirma, from the launch pad.

Since then, the company has consistently introduced new iterations of the brand, such as the 2008 introduction of Wheel Active Gold (which mimics P&G’s Tide Detergent in appearance) and the 2009 introduction of Blue Wheel (for coloured garments). Today, Nirma (10%) and Ghari (9%) are the closest competitors.