Iconic Ads: Camel – I’d Walk A Mile For A Camel

It was luck and smartness that the now famous line came from NW Ayers’ Armistead, who smartly used the line for the brand.

William M. Armistead, of NW Ayer, got the Reynolds account starting with Lord Albert pipe tobacco. He is credited with creating the modern style of advertising, advocating regular small announcements rather than the usual weekly or annual newspaper announcements.

Like so many industries in the early days of the 20th Century – tobacco also began its development with sectional brands.

In the South-Atlantic, Piedmonts were popular, as were Home Runs and Picayunes in New Orleans. The East and Mid-Atlantic liked Fatimas, and San Francisco sold a brand nearly solely with a “mouthpiece.”

R. J. Reynolds, who had just triumphed over sectional brands in pipe tobacco, making Prince Albert a national bestseller, decided to try the same feat in cigarettes.

Reynolds thought he had created the ideal blend of Turkish and American tobacco for a national cigarette after spending a long time studying the numerous sectional brands. For $2,500.00, he purchased the name “CAMEL” from a small independent corporation in Philadelphia.

He then told Armistead that they were ready to move forward and offered him $250,000 to launch the Camel brand.

This sum was refused, with the following statement: “While it is true that all of those around the Reynolds Tobacco Company who have tried the new cigarette think it is a great blend, some of them may have expressed that belief because they thought it would please you, Mr. Reynolds. If you spend a quarter million dollars on that cigarette – and the public does not like it – you will kill the brand, as well as lose a quarter million dollars. Public approval is the only way to test the product. If this cigarette will not sell without advertising – it certainly will not sell with advertising.”

Armistead then suggested that one carton of Camel Cigarettes be sent to each of Cleveland’s top 125 retail stores. The understanding that the carton would be left on top of the counter and that numbers on repeat orders would be provided.

And there were repeats.

Then, the same system was tried out in other sections of the country where various sectional brands were being sold. Again and again, the product started to repeat without any advertising.

The same technique was then tested in other parts of the country. Without any advertisement, the product began to have repeat sales.

It was obvious from this testing that this new blend could overcome sectional predispositions.

Then advertising was advised for a full-scale launch of the brand.

Sales Divisions, of which there were 87 in the United States, were in charge of this launch. Each Division Manager was told to contact the Home Office as soon as he completed distribution in his territory.

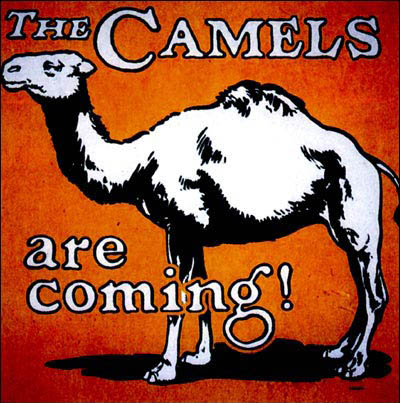

Teaser content in newspapers, typically forty inches in size, kicked off the advertising campaign.

The first ad featured a simple teaser display with the words “The Camels Are Coming” on it. It was a play on the old Scottish folk song “The Campbells Are Coming”

The second advertisement featured the wording “Tomorrow’ There ‘ill Be More Camels in This Town Than in Asia and Africa Combined.”

The third advertisement stated “Camels Are Here,” and went on to describe the brand.

From then on, newspaper space was used on a campaign centered on the idea that Camel Cigarettes did not offer any premiums. Though common with most cigarettes at the time. The cost of the tobaccos used in Camel was too high to allow anything other than the high-quality product itself.

Except for New York City, camels began to move quickly in practically every location. That city had been relegated to the end of the line. The Metropolitan Tobacco Company, which had advised the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company that if they kept their salesmen out of New York City, they would give them distribution in about 17,000 top-rated stores in one week – as soon as they were convinced the product would sell.

Reynolds agreed. In Newe York, employing the same strategy – with advertisements appearing in magazines and billboards in addition to newspapers, but with the same hard-selling premise.

Camels rose from fourth to first place in five years, capturing a substantial portion of the cigarette market.

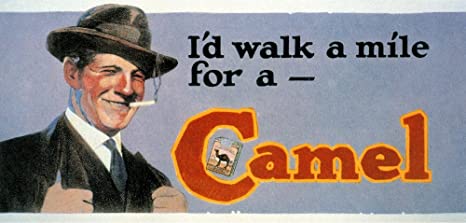

One of the most memorable phrases in the cigarette wars arose from an interesting experience.

One day, a sign painter was working on a billboard when a man approached him and requested if he could give him a cigarette. The painter offered him a Camel. “I’d Walk A Mile For A Camel,” the stranger responded, thanking him enthusiastically.

The sign painter was astute enough to sound out the agency about the potential billboard idea, and one of the best and most well-known advertising slogans arose from it.

Credit goes to Armistead to recognise this line and use it everywhere.