Iconic Ads: Lucky Strike – Reach for a Lucky

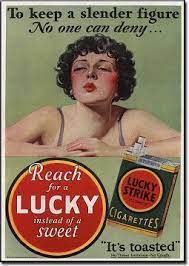

Slimness was added to the list of modern traits that the cigarettes claimed to have: “Reach for a Lucky” instead of a sweet.

The first suggestion Lord & Thomas (the advertising agency) gave their client American Tobacco must have flummoxed them: stop advertising most of your brands.

Albert Lasker was handling the account for Lord & Thomas. He claimed that the corporation needed to create one tremendously powerful product that could compete with Camels and Chesterfields, rather than a slew of modestly successful minor brands. “You can’t survive without this one brand,” Lasker remembers saying, “because this one sort of cigarette accounts for 80 or 90 per cent of the cigarette business in this country now.”

“These other cigarettes and products were a different kind of product altogether. Rather than spending a modest or a moderate amount of money on any of these fifty items, milk them all. Take the money you spend on them and the income you get from them and put it into a huge push for Luckies.”

George Washington Hill, the Lucky Strike brand’s manager and the son of American Tobacco CEO Percival Hill, concurred. As a result, funds formerly spent on advertising Blue Boar (the original Lord & Thomas account) and most other minor American Tobacco products were redirected to Lucky Strike.

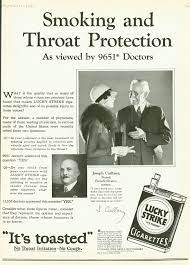

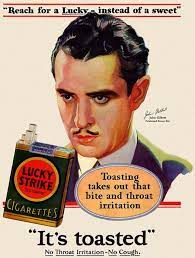

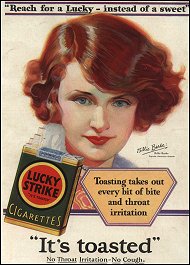

The initial Lord & Thomas campaign for the now-favourite brand was based on the concept of “toasting,” which aimed to distinguish Luckies based on how the tobacco was prepared. The copy emphasised the benefits of toasting, such as better flavour and lower acidity, which should make it easier on the throat. Though the tobacco used in Lucky Strikes was heated to somewhere between 260 and 300 degrees during the manufacturing process — this was standard practice in the cigarette industry at the time.

Because the brand wasn’t performing well enough to fulfil Hill’s high expectations, Lord & Thomas began supplementing the “toasted” motif with a series of advertising known as the “Precious Voice” campaign in 1927. This new promotion claimed that, in addition to making cigarettes easier on the throat, toasting also helped protect the throat and voice.

The target demographic for “Precious Voice” was one of the things that set it apart. The societal stigma against women smoking was still strong at the time. Even though Philip Morris introduced the first women’s cigarette in 1924 (saying it was “as light as May”), few women smoked openly, and most restaurants and other public places forbade women from smoking.

As women began to smoke in the home, Lasker knew that a huge new market was about to emerge. It had him convinced one afternoon as he was having lunch with his wife at the Tip Top Inn, a restaurant near his Chicago home. Flora had a tendency to put on weight, and her doctor had advised her to start smoking to help her lose weight. However, when she attempted to light up after lunch, the owner hurried over and claimed he couldn’t allow a lady to smoke in the main dining area. He went on to say that if Flora wanted to smoke, the Laskers would have to go to a private room.

“It filled me with indignation,” Lasker recalled, “that I had to do surreptitiously, something perfectly normal in a place where I had gone so much. That determined me to break down the prejudice against women smoking.”

Without a doubt, the promise of doubling Luckies’ potential market affected his decision. Lasker presented his proposal to George Hill, telling him that if American Tobacco took immediate action, the women’s market might be theirs.

This choice resulted in Precious Voice, one of the few postwar efforts that were completely planned and supervised by [the aged] Lasker. Lasker felt that testimony from well-known foreign ladies could help erase prejudice against female smokers, so he began with opera singers. “My thoughts naturally went to the opera stars,” he recalled, “since there were just a few American stars at the time, and the rest were international.” And if I could get the women of the opera, I’m sure I’d be able to get the women of the theatre in no time.”

The subtext, of course, was that women who made their living as singers were ready to entrust their priceless voices to Luckies.

Precious Voice was one of the earliest Lord & Thomas advertising efforts to extensively rely on testimonials, and the campaign swiftly grew to include nearly all of the stars of the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Stage and cinema talents (including women and men) hurried to join the chorus of artists applauding Luckies, just as Lasker had predicted. Surprisingly, none of the people who testified for Luckies was compensated for their time; they thought the free publicity was enough.

The advertising was a huge hit right away. “Like the land in a boom field where oil has just been discovered,” Lasker later boasted.

Hill worked with Lasker to continue exploiting technological development, celebrity endorsement, and the New Woman to identify Luckies with modernity, despite the criticism of testimonials and dubious claims in Lucky Strike advertisements. Observers noted that the taboo against women smoking in public had been greatly eroded in the months since Lucky Strike began directly targeting women in 1927. In a new campaign with a new slogan for Lucky Strike in 1928, slimness was added to the list of modern traits that the cigarettes claimed to have: “Reach for a Lucky.”

Hill allegedly came up with the Reach for a Lucky promotion following a fortuitous encounter on the streets of New York City, according to company lore. “I was driving out to my house and came to 110th Street and Fifth Avenue; I was sitting in my car and peered around the corner, and there was a large, stout lady chewing gum.” Hill said, “And there came a taxicab…coming the other way.” “In the taxicab, there was a young lady with a long cigarette holder in her mouth and a very good figure.” “It hit me right then and there,” he added, “there was the stout lady chewing, and there was the slim young girl lighting a cigarette.” A memorable phrase came to George Hill’s mind at that very moment: “Reach for a Lucky Instead of a Sweet.”

Other tales of this genesis storey attribute the slogan’s creation to Albert Lasker, and some even claim that the two created it simultaneously and independently. Hill instantly approved the tagline and made it the new selling point in Lucky Strike advertising, regardless of who came up with it first. The new campaign received the lion’s share of American Tobacco’s advertising budget. The slogan “Reach for a Lucky Instead of a Sweet” implied that Lucky Strikes were a healthier alternative to candy and other unhealthy items. Another reason-why argument, similar to the Precious Voice campaign, was used to persuade regular women to smoke Luckies, and to smoke them more frequently. Lucky Strike was marketed as a product that might help customers become more “contemporary,” with a single phrase combining health concerns, slimness, and “female vanity.”

Sales of Lucky Strike increased at a breakneck pace. The Precious Voice marketing helped raise Lucky Strike sales in 1927, but it didn’t bring them anywhere near the number of Camels or Chesterfields sold. The next year, with the help of the Reach for a Lucky Instead of a Sweet tagline, over 40 billion Luckies were sold, placing them second only to Camel in terms of sales.