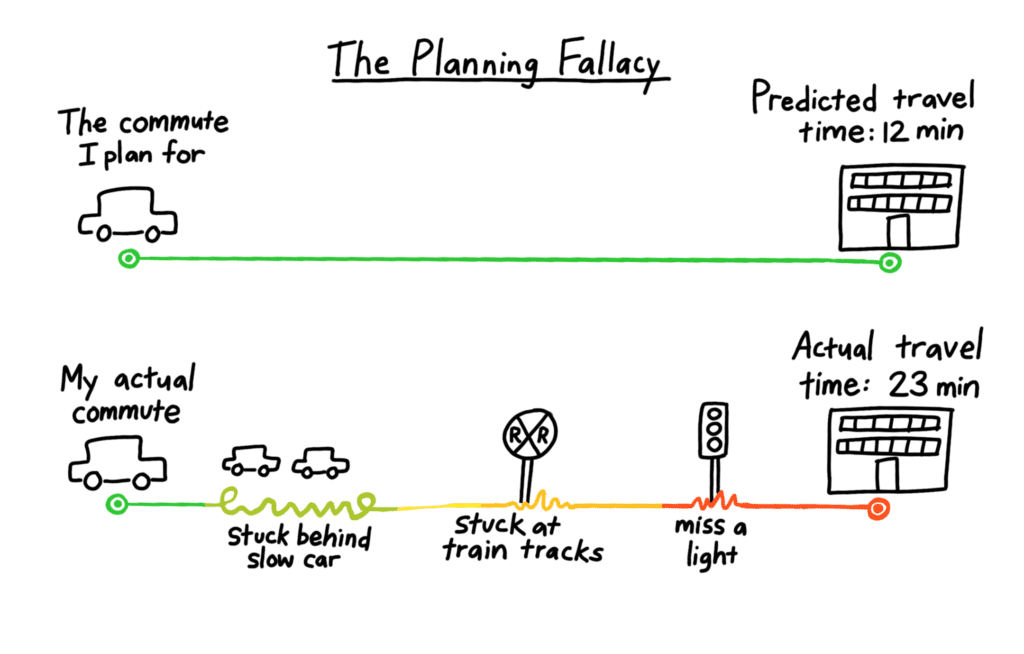

Planning Fallacy – Underestimating how long it will take to complete a task

This the tendency for individuals to overestimate their ability to finish a task in the future, despite the presence of evidence to the contrary.

It is routine for a coworker who has been tasked with completing a presentation by a certain date to fail to do so within the allotted time frame, even though they had previously completed identical tasks. To your chagrin, the due date was extended.

The Sydney Opera House, one of the world’s most recognisable landmarks, took a full decade longer to build than originally anticipated due to several complications and setbacks. A total of $102 million was spent to complete the project, which was initially estimated to cost $7 million.

The Australian government was adamant that the building get underway quickly so that they could get to work while support for the Opera House was high and money was still available. But since the architect hadn’t finished the final drawings, serious structural difficulties had to be fixed later, which slowed down the process and increased the cost. Unfortunately, the iconic shell form of the House’s roof required a complete rebuild of the podium since the previous design was not sturdy enough.

Afraid that political opponents might attempt to halt the building of the Opera House, politician Joseph Cahill hurried its progress quickly. Out of his zeal, he ignored the project’s detractors and instead made expense estimates based on his gut feeling. It would have been wise to slow down and take the big picture into account in planning since the final structure turned out to be magnificent and unique.

Definition

The term “planning fallacy” was coined by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979 to describe a kind of cognitive bias. Overconfidence in one’s ability to finish a task in the future was described as “the propensity to underestimate the time required to complete a future activity.”

Due to this misconception, we may construct bad long-term plans in which we fail to account for the true time and effort requirements of a project. It also causes us to place an exaggerated amount of stock in our skills while minimising the roles of chance and serendipity.

Why it happens

- We’d rather look on the bright side of things.

Our natural tendency to overestimate our talents is at the root of the planning fallacy. Most of us have a generally upbeat outlook. We tend to prioritise positive information when making decisions; this includes having a positive outlook on the world and other people, remembering happy occurrences more vividly than bad ones, and expecting a favourable outcome from most situations.

- When it comes to evaluating our skills, we are notoriously inaccurate.

As a result of these biases, we often overestimate our abilities and those of our team members when we embark on project planning, and we tend to concentrate on idealised outcomes rather than probable problems. Optimism is crucial for success, but it may backfire if it clouds people’s judgement and cause them to ignore practical considerations.

- Become anchored to the blueprint

Anchoring occurs when we make snap judgments based on incomplete or biased data. We are predisposed to think in terms of the timelines, budgets, and other parameters that we set for ourselves when we create the first plan for a project.

If our initial expectations were too hopeful, anchoring might become a serious issue. It’s hard to let go of our original projections, even if they turned out to be wildly off. For this reason, we tend to make only modest revisions to our plans as we go along, rather than addressing any serious issues that may arise.

- Ignoring unfavourable details.

Even if we do consider information from the outside world, we often disregard negative opinions or statistics because they threaten our positive worldview. The other side of our positive bias is that we tend to avoid thinking about the negative aspects of situations.

The term “competitor neglect” is used to describe the phenomenon when corporate leaders fail to consider the actions of their competitors because they are too preoccupied with the affairs of their firm.

Further, while analysing our achievements and failures, we often attribute them to the wrong factors. To a greater extent than we do with happy results, we prefer to blame unfavourable ones on other forces. This makes us less likely to learn from our mistakes since we tell ourselves that the external causes that led to our failures in the past won’t arise again.

- Social pressure

In a competitive work environment, employees who express less enthusiasm for a project or who insist on a lengthier deadline than their peers may pay the price. However, bosses may reward those who make the most positive forecasts, encouraging people to rely on their gut instincts rather than data.

How to avoid it

Merely being aware of the planning fallacy is not enough to stop it from happening. Even if we have this knowledge, we still risk falling into the trap of believing that this time, the rules won’t apply to us. Most of us have a strong preference to follow our gut, even if its forecasts have been wrong in the past. What we can do is to plan around the planning fallacy, building steps into the planning process that can help us avoid it.

- Look at it from the outside

The planning fallacy occurs when we ignore external information regarding our chances of success in favour of our intuitive estimates of the project’s cost. Many of us are guilty of this, unfortunately. We tend to favour looking ahead in time than looking backwards since planning is primarily a forward-looking endeavour. As a result, we start to forget about the lessons of the past.

- Improve your estimations by making use of the segmentation impact.

Planning for the completion of smaller subtasks rather than the completion of the whole project is a comparable method that entails splitting up large projects into their component pieces. Although humans are notoriously poor at anticipating how much time would be needed to complete major projects, studies have shown that we are extremely good at preparing for little ones, with forecasts that are frequently amazingly accurate and, at worst, overestimates. Therefore, this is the safest course of action: In actuality, it’s preferable to devote more time to a task than is necessary.

- Put information to good use.

The first step in avoiding the planning fallacy is maintaining an accurate record of past projections and actual results. If you keep tabs on how you’re doing, you’ll be able to see where you’re excelling (or failing) and where you need to work harder.

For example, you want to know how long it takes to complete a project like this. Other options include polling your staff or looking at statistics tailored to your field.

Predictive analytics and machine learning may also be of assistance. Predictive maintenance would alert you to potential problems in the manufacturing process, for instance. You may prevent an issue from arising by using this data to take preventative measures in advance. As a result, there will be no slowdown in output.

- Establish reasonable due dates.

In certain cases, deadlines are seen to have a bigger effect on behaviour than forecasts. Although “people are aware that they have finished past jobs only slightly before a deadline,” they continue to hold out hope that they will complete the present assignment on time.

The trick isn’t to choose any old due date and call it a day. The key is to create a timetable that is achievable, but challenging enough to motivate you to complete the task within the allotted time. Have previous deadlines proven difficult to meet? Here are some suggestions to help you get started.

- Do not forget Murphy’s Law.

All things being equal, most of us err on the side of optimism when making time estimates. Despite your best preparations, unexpected challenges are certain.

Being a little bit pessimistic may help in certain situations. Predicting and avoiding problems is much easier with its guidance. To anticipate every possible outcome would be impossible.

- Try out three-point estimates.

Having you choose three pieces of information, the “three-point estimate approach” makes you face your potential optimism head-on. This includes:

- Best-case scenario estimate

- Worst-case scenario estimate

- Most-likely scenario estimate

Since we have a bias toward optimism when making estimates, the best-case scenario estimate will most likely coincide with your original guess. Your experience with comparable endeavours may provide the best indication of what is likely to occur. How long something may take in the worst-case situation is also important to think about.

Get things done and stop putting things off.

Even if you’ve taken these steps, it’s difficult to concentrate when so many other things are competing for your attention. Cut them down to size as much as possible. I’m referring to the typical culprits, such as phone alerts and chatty coworkers. However, you should know that when your brain wants a break, it starts to wander. To combat this, scheduling regular breaks and utilising the Pomodoro Technique may be quite helpful.

Reference