Iconic Ads: Honda – You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda

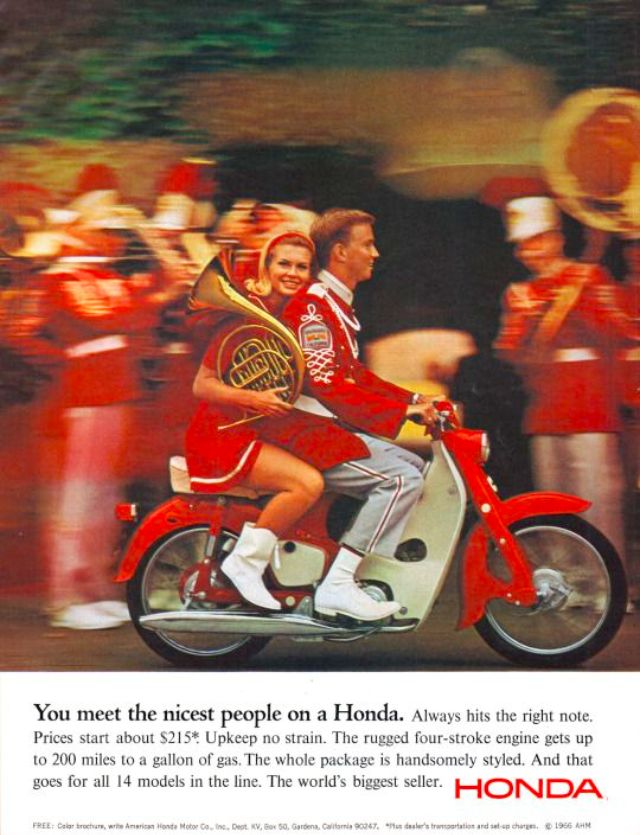

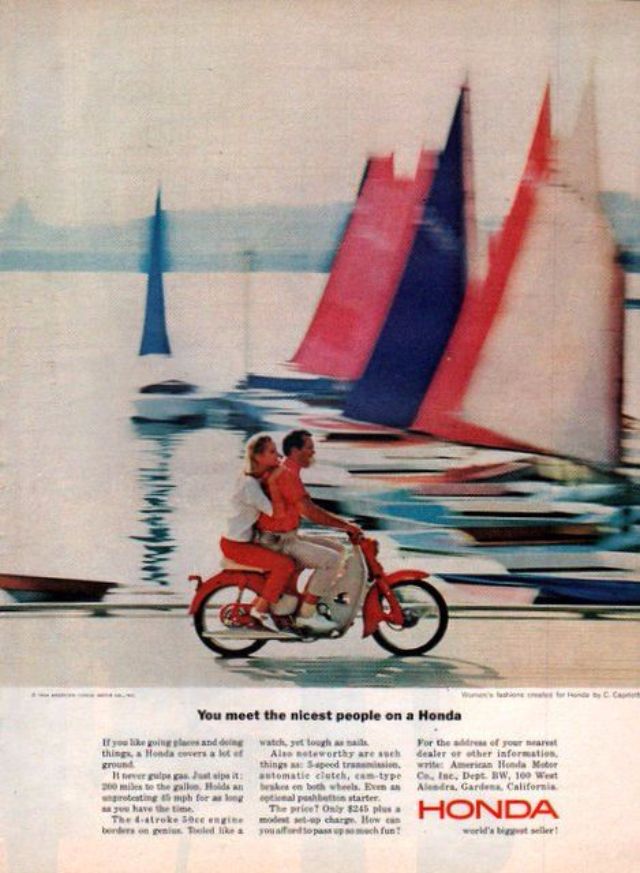

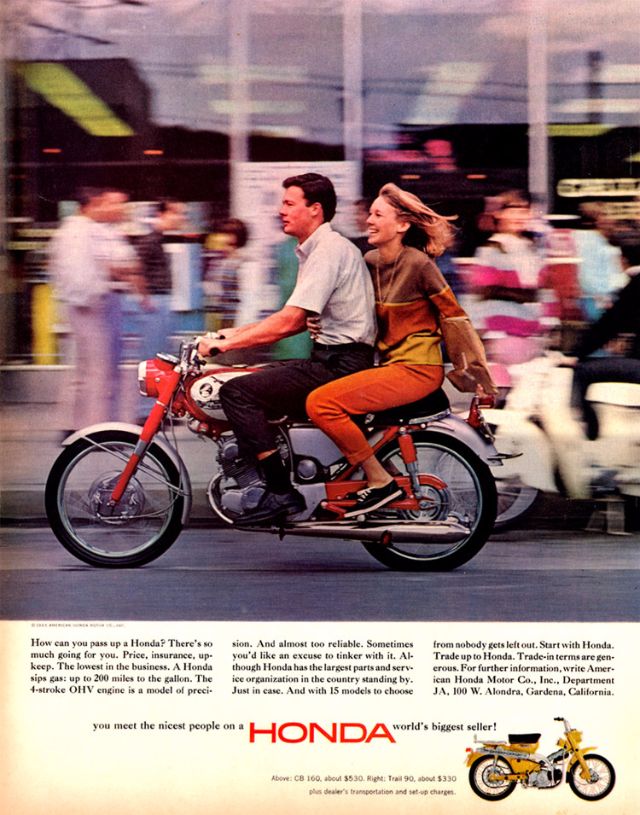

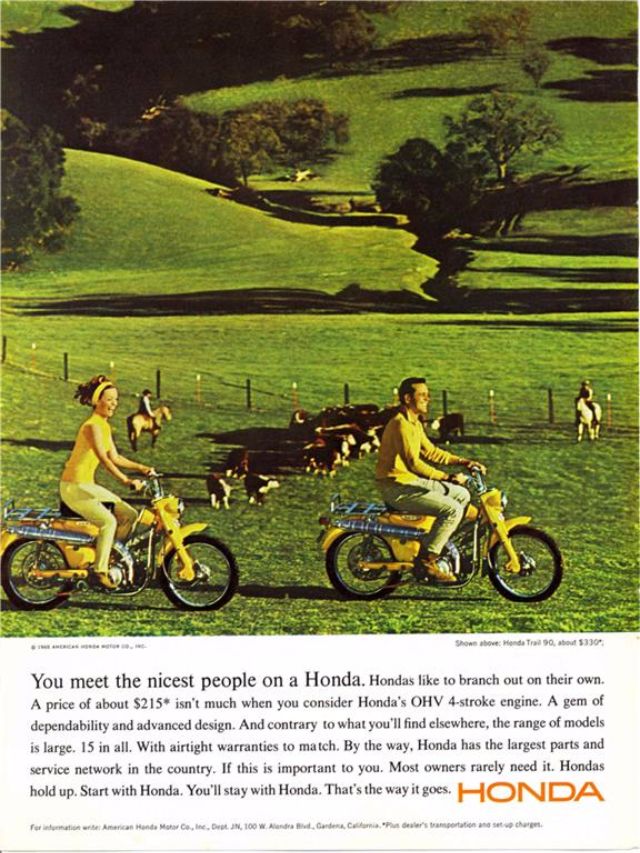

Countering popular perception, Honda created different imagery of a biker through the “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda” advertising.

Most of the American public had an aversion to bikes and all things linked to riding after the 1947 “riot” in Hollister, California and the start of the Hells Angels motorcycle club. This was also emphasised by the 1953 Marlon Brando movie “The Wild One”

Post-war and most of the 1950s, motorcycling seemed to be the territory of serious hobbyists and illegal motorcyclists. There was no such thing as serious motorcycling at the time. Popularity was limited because of their problems like leaks & high maintenance requirements.

The Scenario

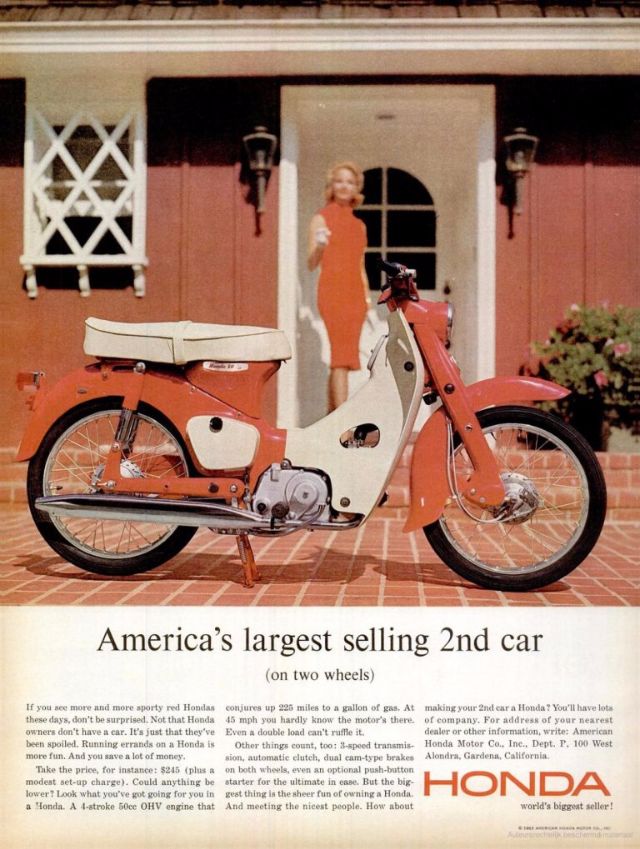

In 1959, the total number of motorcycles imported into the United States amounted to 6,300. American Honda, Honda’s U.S. distributor, was established in Los Angeles the same year. Honda Motor Co. had made a big move when it decided to go worldwide with its fledgling business. Kihachiro Kawashima, who headed Honda’s Special Planning Division in 1958, first advised the company to begin its worldwide march in the predictable Southeast Asian market. But when he asked Soichiro Honda’s business partner and right-hand man Takeo Fujisawa for his feedback, Fujisawa stated that America was the target market for Honda Motor. The Super Cub, a step-through 50cc motorcycle with a 3-speed semi-automatic transmission, was launched by Honda in the same year.

Fujisawa went on a tour to meet with an American import distributor about the logistics of the company’s sales efforts overseas. According to stories, Honda planned to ship 7,500 vehicles to the United States, When asked, the distributor scoffed saying that no company sold that number yearly, and Fujisawa gently informed his host that Honda intended to sell those many bikes in one month!

For the first two years, American Honda’s sales pace fell short of Fujisawa’s expectations, despite being good compared to other brands in the U.S. market.

Sporting goods stores and a select group of dealers carried the Cub 50. Dealerships sprung up as Hondas became popular. Various periodicals, including Popular Mechanics, ran advertisements for the “Nifty, thrifty, Honda 50” bikes.

With a total of 750 dealers at the end of 1962, American Honda was selling more than 40,000 motorcycles a year, more than any other motorcycle manufacturer at the time. A target of 200,000 units was established for the next year, a sum five times more than the previous year’s sales record. American Honda’s employees were taken aback by the challenge. For Kawashima, this wasn’t an impossibility as long as motorcycle riders’ public reputations were improved and the product’s name was better known. It wasn’t enough to produce reliable, easy-to-ride, and visually appealing motorcycles. Honda needed to make a bold effort to sell motorcycles to people who weren’t riders or bikers to push this newcomer on the American motorcycling scene into prominence. As a result, he was prepared to spend a large sum of money on it. Kawashima was prepared to spend the most money ever – $5 million

Advertising

Enter Grey Advertising. They hired a strong young creative director Robert Emmenegger, to lead the team on the Honda account. It was his commercial film and television experience, as well as his broad musical skills, that allowed him to create a campaign that was effective in meeting its objectives. With this new perspective on how to market motorcycles to students and young people, he was able to get a leg up on the competition. While Emmenegger was in charge of Honda’s media advertising, it was clear that television advertisements were his expertise. Music and lyrics were frequently composed by him in the times ahead.

Rewind. When a UCLA lecturer referenced an assignment made by one of his marketing students, to a Grey executive – “You meet the nicest folks on a Honda.” An apt and simple thought. Grey secured the slogan’s rights before submitting it to American Honda. Kawashima loved the advertising campaign and brought it to Fujisawa and Honda. Few people know what their initial reaction was to it, but ultimately they gave their blessings. And sales exploded.

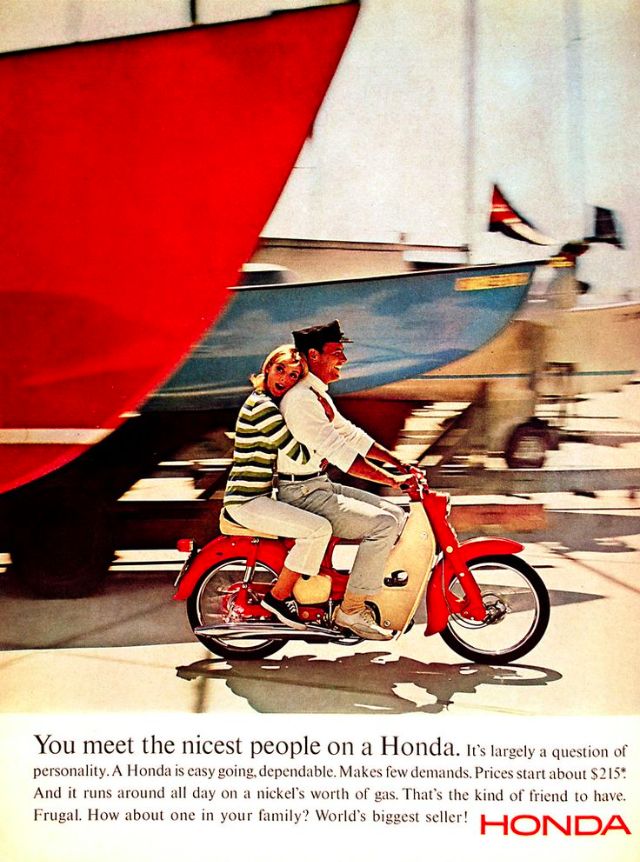

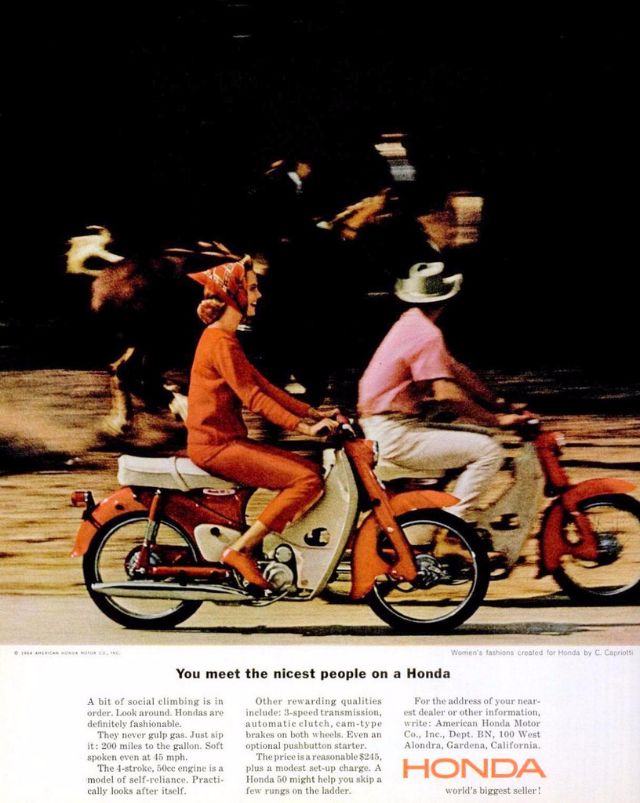

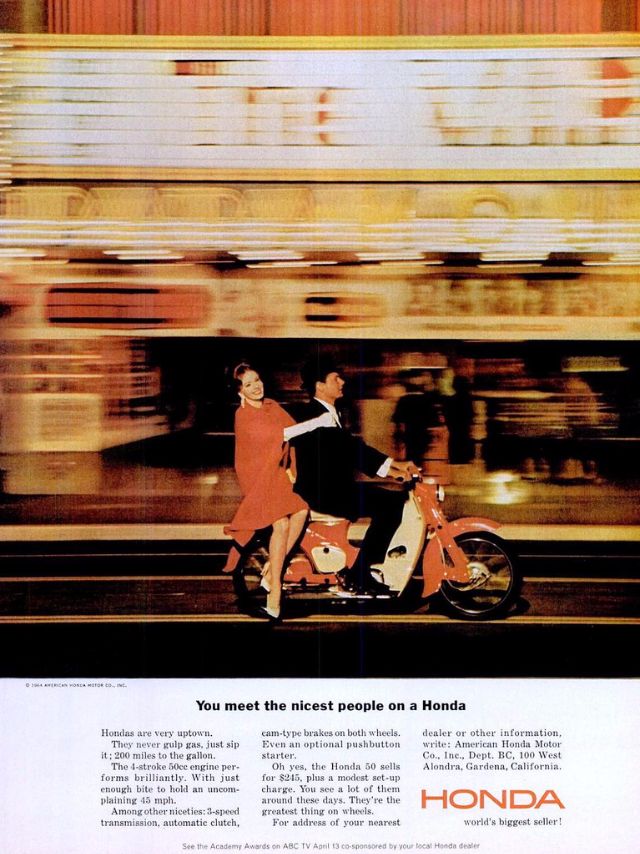

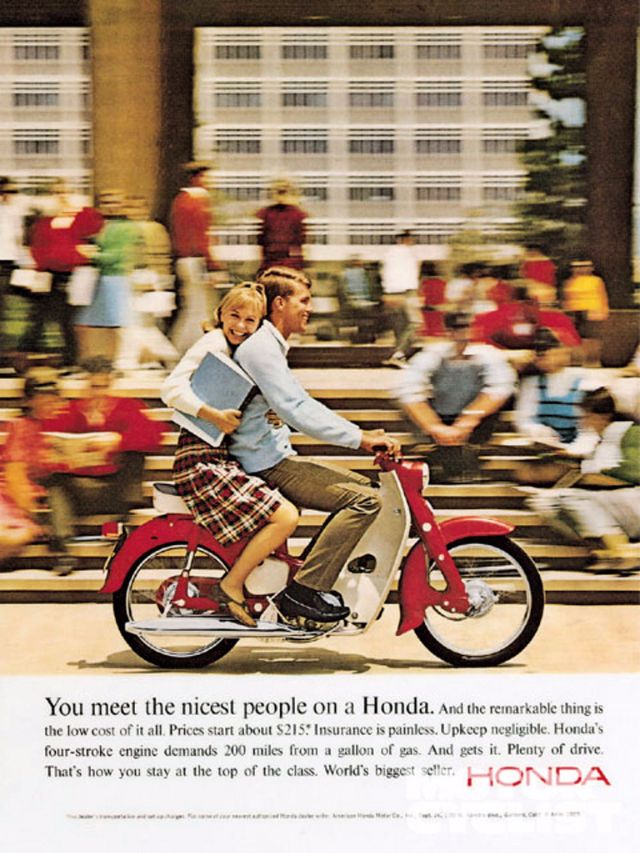

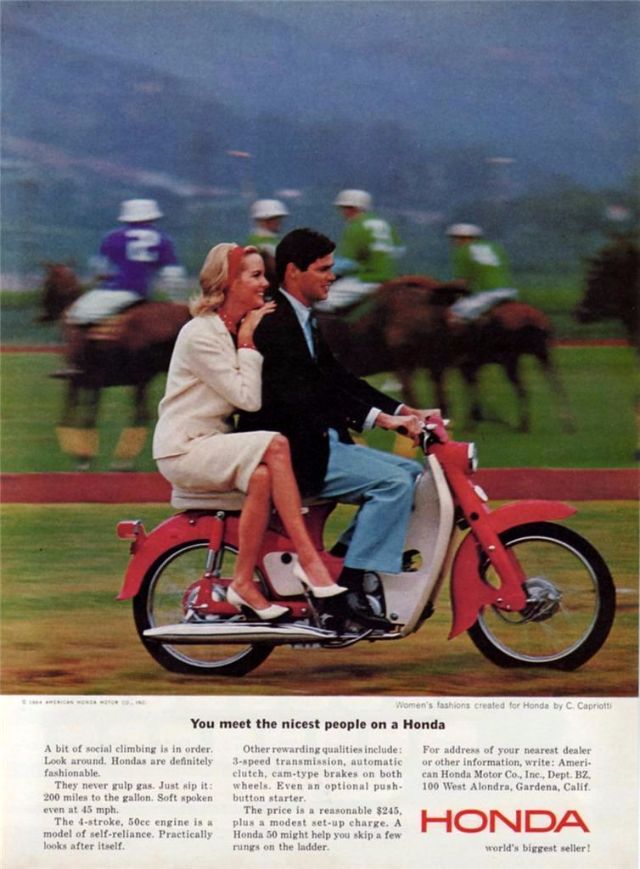

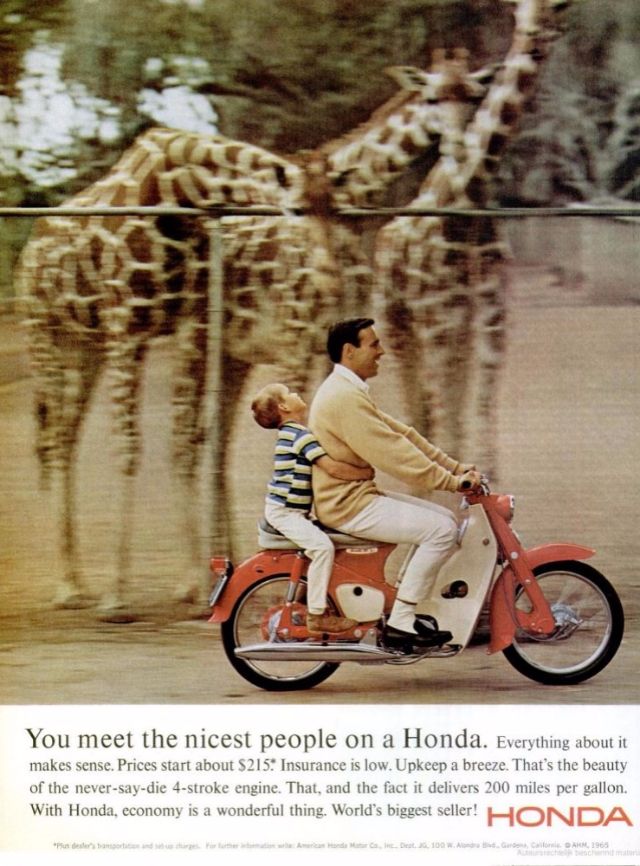

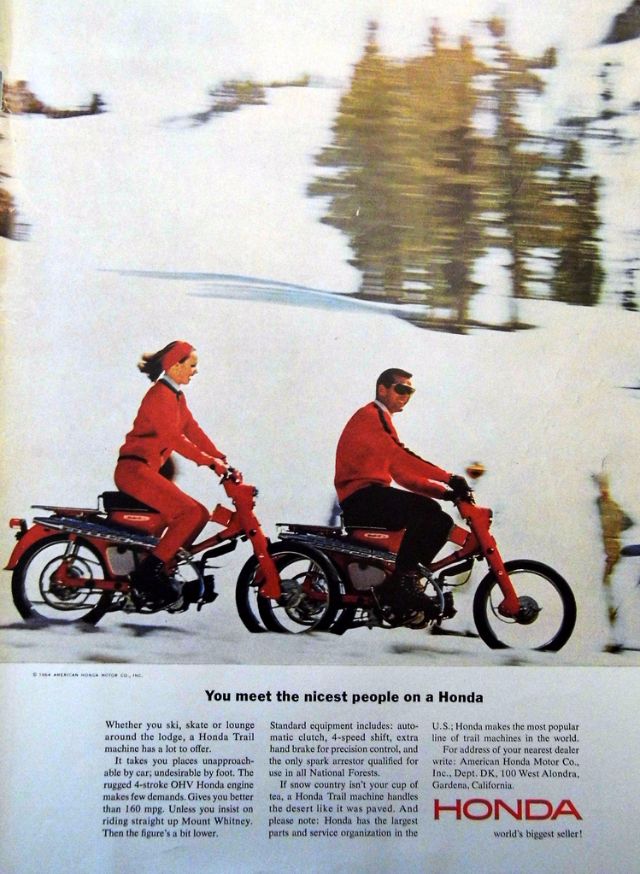

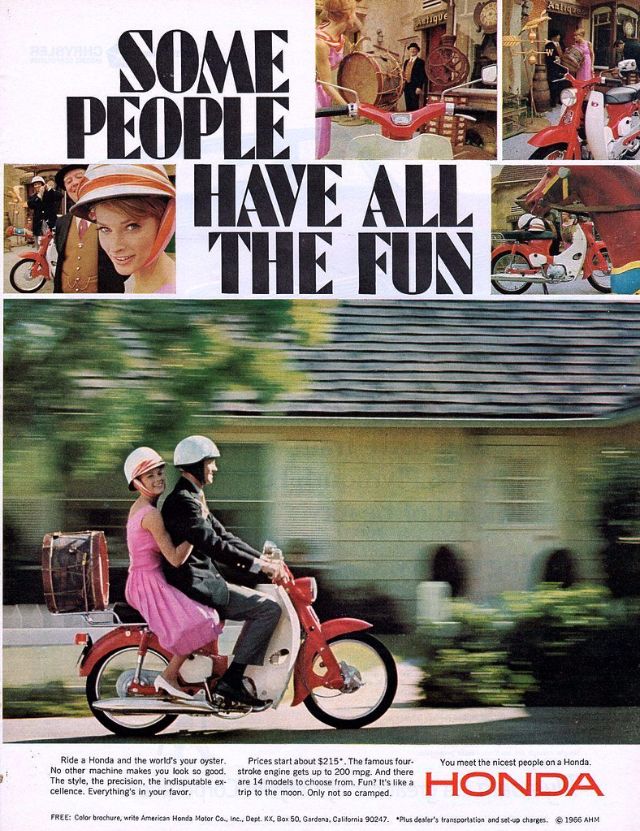

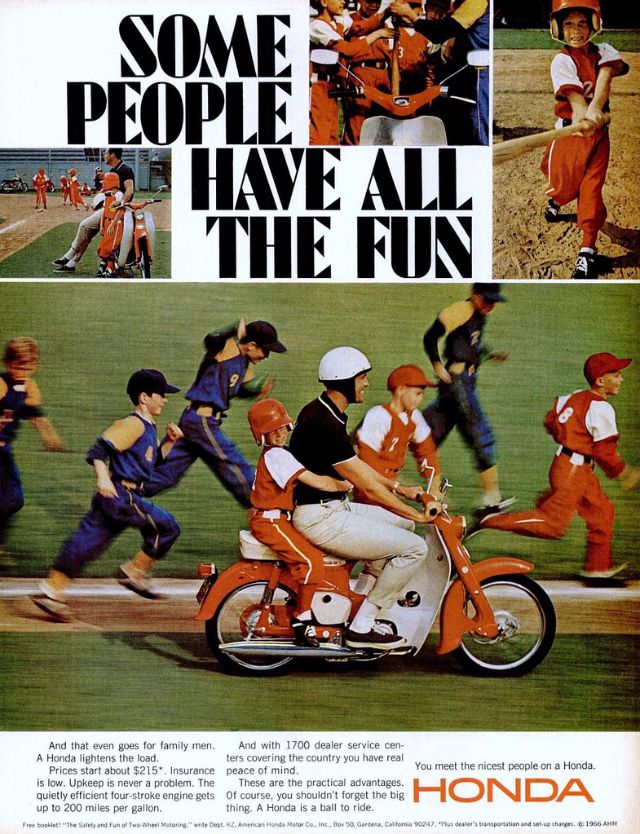

To promote the Honda 50, a range of respectable people like a parent & children, housewives, young couples etc – called “the nicest people” in the commercial – rode them for a variety of purposes. In addition, the vibrant artwork and polished layout drew in a large audience. It wasn’t long before those who had previously shunned the idea of owning a motorcycle began to see it as a convenient and casual mode of transportation.

When adolescents begged their mothers to purchase them a motorcycle, they used to answer, “I’ll buy you one, but only if it’s a Honda.” Even as a gift for birthdays and Christmas, the Honda 50 became a popular choice. And the motorcycle was ultimately recognised as a popular product thanks to the support of an ever-widening segment of the American public, ranging from students and housewives to businesspeople and outdoor enthusiasts.

In the campaign, the Super Cub’s design features like the chain encasement – which prevented the chain lubricant from flying over the rider’s clothing; the leg shield – which stopped road debris and also masked the engine and semi-automatic transmission was crucial. An identity shift to present the Super Cub as a consumer appliance that doesn’t necessitate mechanical aptitude, because earlier a biker or motorcyclist was the domain of few in black leather jackets and aggressive demeanour.

The song “Little Honda,” written by Brian Wilson and Mike Love in 1964, extolled the joys of riding the Honda 50 and even invited the listener to visit their local Honda dealership, in language that sounded like it could have been written, or at least paid for, by Honda’s advertising copywriters, but it was not a commercial jingle. Followed by the release of the Beach Boys’ original recording in 1964. In 1965, as a B-side to their recording of “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda,” The Hondells recorded another song “Sea Cruise” promoting the Super Cub. This was used in television commercials.

Results

It was the goal of the ad campaign to improve the public perception of motorcycles and increase the overall size of the motorcycle market. Rather than relying on the macho approach of most motorcycle advertising at the time, Honda created new ground by appealing to a broader demographic of purchasers.

The Honda 50 had been a huge hit with the general population. It was more than just another motorcycle; instead, it represented a new concept in everyday transportation. In doing so, it removed the motorcycle’s long-held image as a vehicle of evil and unhappiness.

Long-running campaigns with the line and the music, as well as images of respectable middle- and upper-class individuals riding Hondas had become synonymous with the Honda brand ever since they were launched. Contrasting with the one percenter “bad guy” bikers, Honda’s image became the main point of Japan-hating Harley-Davidson.

“The Nicest Things Happen On A Honda!” became another line as a result of the successful multi-year advertising campaign. In 1963, more than 148,000 Hondas were sold, with the Super Cubs leading the way. The next year, Honda dominated the U.S. market by more than 50%.

The popularity of Honda’s campaign didn’t just resonate with Harley-Davidson fans, but also with the company itself albeit a little conflicted. For a while, the idea that Harley-Davidson riders weren’t “good people” upset them. Harley had tried to cultivate imagery of respectability. It would be another ten years before Harley-Davidson began to tentatively embrace the “outlaw” demographic of their client base. In 1964 by denying any affiliation with one-percenter bikers they left away from the impact of the Honda campaign. Ads for both Vespa and Yamaha soon followed, which were similar to Honda.

8 Comments